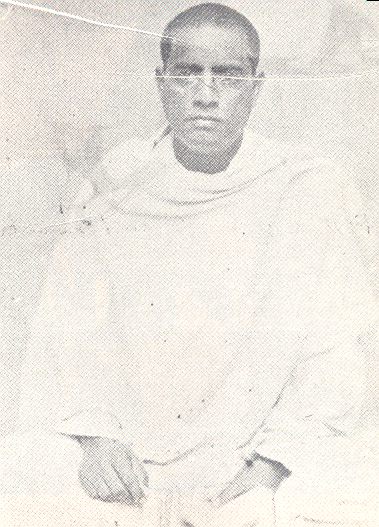

BRAHMABANDHAB UPADHYAY

(1861-1907)

Theologian of Inculturation

Gispert-Sauch G.

Among the pioneers of Indian Christian theology, Brahmabandhab Upadhyay is a towering figure. He was a Brahmin convert at the turn of last century who dreamt of a truly Indian Church freed from the remnants of colonialism, drawing on the Vedanta and other areas of Indian religious thought. He was a pioneer in journalism, education, inculturation and the ashram movement.

As we enter into the Third Millennium we remember a great Indian convert, Brahmabandhab Upadhyay, who at the turn of_the century lived also in a crucial moment in the history of our countryand participated in it wholeheartedly. Precisely this year marks the centenary of the publication of his most enduring gift to Indian theology and to the Indian Church, the "Canticle to the Trinity", as he called it, the Vande Saccidanandam, a gem of Christian hymnology which became the property of all Christians in India specially when it was so beautifully sung in the presence of Pope Paul VI during the International Eucharistic Congress of Bombay in 1964.

Whether Upadhyay deserves the title of "Father of Indian Theology" at times given to him, can be debated. There was surely Indian theology already before him in the land that received the message of Jesus from the earliest centuries. The liturgy of the St. Thomas Christians contained an implicit theology; Robert de Nobili composed learned treatises in Tamil and perhaps other languages which cannot be forgotten in an authentic history of Indian theology. There was also some important poetry that could legitimately claim to be theology: Stephen's Krista Purana, Beschi's Tembavani, Arnos Padiri's Puthanpana, to which one must surely add hymns produced by Indian Christians in various languages like those of the Tarnil Antony Kutty Annviar. There was also a respectable output of Sanskrit Christian poetry part of which has recently been made available with translation (Amaladass, Young, 1995). Nor must we forget the writings in Persian by Jerome Xavier and in Tibetan by Ippolito Desideri, in North India both addressed directly to non-Christian audiences, Muslim and Buddhist respectively.

Brahmabandhab strides the century with a colourful life already recounted in its essentials by The Blade.of Animananda, and will soon be made available in a more scientific work of the scholar who today best knows Upadhyay, Dr Julius Lipner.

Upadhyay was born into a Brahmin family of Khannyar,a village 55 kms north of Calcutta in 1861 and was given the name Bhavanicharan after the family's tutelar deity, Kali. His father's occupation implied frequent changes in the family location and Bhavani went through a series of English schools then flowering in India. In one of them he came to know about Jesus Christ and the Bible. But he was more keen in the traditional culture of India and made sure he acquired a good knowledge of Sanskrit that would prove important in his life. An intense love of the tradition and culture of India and a passionate love for Jesus, when he surrendered his life to him, form the two pivots on which his short life hinged.

In Calcutta Upadhyay became the friend of Narendra Datta (later known as Swami Vivekananda) and the Brahma Samaj leader, Keshab Chandra Sen who had.a.deep influence on him. Sen was attempting an “Indian Church" the "New Dispensation" on the basis of Hindu Unitarianism and Vaishnava devotionalism, but centred around the person of the "Asiatic Christ", not the Christ of the foreign Church. The movement was religiously syncretic and socially reformist and egalitarian.

A chance reading of Faa de Bruno's classic, Catholic Belief while keeping vigil at his father's death bed in Multan made him decide to embrace fully the Christian faith. He received baptism at the age of 30, in February 1891. In September of the same year he officially joined the Catholic Church attracted, probably, by the idea of universality implied in its name. He would soon make his own the classic "Catholic" distinction (not opposition) between natural and supernatural truths and the natural and supernatural order which he used in his own incipient theology of religions.

In January 1894 he started a monthly, in many ways the first Catholic theological journal. of India, Sophia a journal of inculturation ,dialogue and mission. For more than five years he brought out this monthly almost single-handed, a publication that explained to educated converts but also to Hindus the meaning of Christian life in the context of India. It is mostly in this monthly that Upadhyay articulated his interpretation of Christian truth and where in October 1898 he printed his Vande Saccidanandam—Two and a half years later he published-- another Sanskrit stotra, a hymn of praise to the Incarnate Logos.

At the end of the century there was a lively religious ferment in India, and a strong intellectual interaction between the Hindu and the Christian traditions, at times in the form of dialogue, often in the form of debate, as perhaps there has not been any since. The religious and theological debate was part of the new emerging culture that was struggling to formulate the Indian identity and its goals amid the tribulations of the Raj. Quite a number of small journals were engaged in debate, often apologetic. Sophia debated with them. Upadhyay also sought the oral debate even with the high profile figure of Annie Besant on the public platforms. Rationality was still respected at the time and the criterion on which proposals and counter-proposals were evaluated was logic. Upadhyay's work may be considered primarily as that of an apologist.

It was only during the first decade of the new century, perhaps because of the upheaval produced by the famous partition of Bengal, that the public religious discourse gave way to an exclusively political discourse. It was not necessarily a secularist discourse - certainly not with the arrival of Mahatma Gandhi on the Indian political scene in 1915 whose discourse was both political and religious or, if one prefers, spiritual. But this discourse was no longer inter-denominational and did not have the sharpness of the philosophic and dialectic language of the earlier times. Paradoxically, perhaps, the lines of the religious divide in North India were sharpened by isolation and fear to meet the other. The Temple, the Mosque, the Church and the Gurdwara did not make any further attempt to convince or even to understand one another. One can only speculate on what the history of subcontinent might have been if the older tradition of courageous interchange and honest debate had continued.

Consequent with his natural/supernatural distinction, Upadhyay could claim himself to be, as his uncle had done already, a Hindu Catholic: "We are Hindu so far as our physical and mental constitution is concerned; but with regard to our mind and souls we are Catholic. We are Hindu Catholic" (Lipner and Gispert-Sauch, 1991 XXXVII).Or in the other formulations, "Hindu by birth, Catholic by rebirth; Hindu by race and culture, Catholic by faith".

Today this is the discourse of the "Saffron Brigade" or at least of some of its intellectuals. Just a few years ago Mr. K.R. Malkani, now an MP for the BJP, spoke in almost identical terms to the Faculty of Vidyajyothi :All Indians are Hindus - Christian Hindus, Sikh Hindus, Muslim Hindus...The significance of the inversion apart, today the expression is used in a new political context that makes it unacceptable to most Indians, whether Hindus or belonging to other religions. Now the expression denies the right of authentic pluralism in the nation and rejects the Indian secular identity which we have developed in the past half a century. The slogan is today the expression of political parochialism. In Upadhyay's lips it was an expression of an authentic inculturation and the affirmation of the universality both of the Christian faith and of the Hindu culture. In his constant dialogue with his ancestral tradition Upadhyay laid stress on various moments of the tradition: Vedic theism in the beginning, Vedantic philosophy for a long time, popular religion and the cult of the avatars towards the end of his life. It was during this last period that he vigorously defended the charming figure of Krishna against the subtle manoeuvres of Farquhar (1903) to assimilate Krishna into the Christian salvation history. Upadhyay defended the right of Krishna to be Krishna, an authentic and historical avatar, a concept he distinguished from incarnation, but perhaps in a language not clear to everybody and which alienated many of the Christian community following him. The effect of this specific lecture in 1904 was to sharpen the tension between him and his closest friend Animananda which had already been strained as a result of his allowing his Hindu students to celebrate a Saraswati Puja in a school both of them were running together, called precisely Saraswati Ayatan. Animananda, more deeply schooled in the biblical tradition, saw this as idolatry. Upadhyay saw it as legitimate worship of God by Hindu students through a symbol sanctioned by the Indian tradition. Another important, element in Upadhyay's Hindu consciousness was caste.Like Gandhi, he identified the varnashramadharna with Indian culture. In a variation of the Purusasuktamyth of the origin of castes (RV X, 90) he saw this institution as an eminently human, rational and apt organization of society at the natural order: "The working class represents the organs of work; the trading or the artisan class represents the senses, in as much as they minister to their comforts; the ruling class corresponds to the mind which governs the senses; and the sacerdotal class whose function is to learn and teach the scriptures and make others worship is a manifestation of buddhi(or intellect). The psychological division of man and society is the natural basis on which this anci

ent system of social polity was framed" (Lipner and Gispert-Sauch, 1991, XXXIX). At the supernatural level, of course, we are all equal, as the Church rightly teaches.

One century later, our perceptions are quite different and we refuseto keep this water-tight separation between the natural and supernatural. This form of inculturation of the Christian faith in the social humus of India would not survive the Dalit revolution. We must add that Upadhyay himself did not hesitate to take to the streets during the Karachi plague and serve all the plague-stricken people irrespective of caste, inspired no doubt by the memory of Jesus. He himself survived the plague. One of his closest friends died in service.

All through his period of growth Upadhyaymet with the resistance of the Church establishment, specially in the person of Papal Delegate, Msgr. Ladislas Zaleski whom Dr. Lipner calls "an unmitigated autocrat Who like to be in control of a tidy ship" (Lipner and Gispert-Sauch, 1991, p.xi), a fatal trait for survival in India. Zaleski did not like a lay Catholic, a Hindu convert without formal theological education above all anti-British agitator, to speak of subtle theological issue and endanger the fragile Christian ship in the country. The need of the British Raj in India may have seemed to him an obvious truth. Zalesk forbade Catholics to read Sophia, both the monthly and the weekly, the Twentieth Century, a paper without the theological ambitions which Upadhyay published with Hindu friends for a few months. Zaleski also overruled the approval that the Bishop of Nagpur had given to Upadhyay to start an experiment in Christian Ashram living and sannyasi..way of life.

A last effort to ensure the survival of his dream of a fully Indian Christianity seems to have been his visit to Rome and England in 1902-3. With Zaleski in India there was little hope of an audience -with the Pope which in fact did not take place, but he lectured or Indian Christianity in Oxford and Cambridge and even planned the establishment of a chair of Hindu Philosophy. Like others, this plan also failed to take shape. Upadhyay was accustomed to failures of this type. A creative role within the Church was thus closed to an enthusiastic and patriotic layman.

The dream of an Indian Christianity required a political move: the ending of the colonial system. As long as colonialism survived, the Christian faith would be in India tied to the colonial power. From that moment he dedicated all his attention to the political arena. Without denying his Christian faith, his milieu .was now the extremist political wing of Bengal. His weapon was still the pen.. He started a Bengal daily,S:andhya., provocatively, aggressive against the British. The paper sold well, though in limited edition: it was written in a racy language that caught the imagination. At this period Upadhyay came under the vigilance of the Police and the Home Department. He was arrested for his edition in 1907 and he decided to defend himself, doing away with the lawyer provided by the Government. Hedid so at the initial stages, but a sudden illness in a remarkably body necessitated an operation for hernia and he died of tetanus o the 27th October, invoking the name of Christ, the Lord, as "Thakur, as he had so often invoked him during his life.

Upadhyay cannot be copied today. But he is a theologian of importance who can teach us something. In spite of his use of theSanskrit language and of being a Brahmin by culture, his dialoge was not arm-chair. He was a karmayogin, as Lipner calls him. He acted first. He wanted to liberate India and travelled to Gwalior twice; he thought of an Indian religious life and became himself a sannyasin and started an ashram; he needed to communicate his ideas and founded journal after journal. He was impulsive, ready to risk, the opposite of the classical "intellectual". His writings touch on burning political and social issues and he was never afraid of entering into controversy. Praxis was first. He was not a 'liberation theologian' before the time, in so far as his starting point was not the economically poor or socially oppressed. But he was, in so far as he spoke from the political oppression of colonialism. He represented a voice from below the political establishment, even if it was a voice modulated by the Vedas and a thought shaped by Vedanta.

Many of his articulations sound superficial today though at that time they must have looked revolutionary. For some time he articulated Thomistic philosophy with the help of the Sanskrit traditionas When he interpreted maya as creatio passiva. This model would eventually form a school through The Light of the East Journal (1922-46) and Johanns' "To Christ through the Vedanta". It-was surely "translation theology", needed perhaps at the beginning, but not satisfactory. In his political writings he was more personal, more vibrant, more creative. But even his theological output itself did not stop at translation: the "Vande Saccidannandam” seems to be true "inculturation" though there arein it elements of "translation".

Upadhyay's contribution to the country's history and the Church is perhaps greater than he is credited for. Speaking of the latter C. Lavrenne, in a thesis of the mid-eighties, sums up three areas of the Church's and nation's concerns influenced by him: (1) Inculturation. During the Marian Congress of Madras in 1921 the Bishop of Guntur relayed the battle-cry of Upadhyay for an Indian Church. The Light of the East echoed the work of Upadhyay. (2) Indian education: his concern for an authentic Indian and integral education found an echo in the official reports of the Government and a concrete model in Shantiniketan which he and Animananda helped begin.(3) The ideal of a Christian ashram and Indianised forms of religious life which he tried for a short time have become the common property of India in the last half a century: Monchanin and Abhishiktanand are for themselves explicitly to Upadhyay. The main means Upadhyay used to influence the Church and the country was the press. Brahmin to the core, his role as teacher was mostly channelled through journals. It is fitting that the first issue of this journal at the threshold of 'The Third Millennium' should include a memory of him who a century ago experimented in so many ways for a deeper understanding of Christ, the Sophia of God, and articulated some of his political thoughts in the Twentieth Century.

Notes

For one of the many commentaries on this hymn see

- Gispert-Sauch, G., 1972.

- The work of Desideri has recently been published with an Italian translation and introduction by G. Toscano.

- Actually ghost-written by Fr P. Turmes on the basis of material left by Animananda, who died before completing his work.

- AmaladassAnand and Young, R. Fox 1995

- The Indian Christian, Anand: Gujarat Sahitya Prakash Animanda B. n.d.The Blade, Calcutta; Roy (c. 1947) Farquhar, J.N.

- 1903 Gita and Gospel, Calcutta. Gispert:Sauch G. S.J.

- 1972 "The Sanskrit Hymns of BrahambandhabUpanhyay," in Religion and Society, xix.Lavarenne,

- Christian n.d. Swami BrahmabandhabUpadhyaya(1861-1907). Theologie chretienne et Pensee& Du Vedanta. Lille: Universite de Lille (polycopied, probably c. 1992.)

- Lipner, Julius and Gispert-Sauch, G.,

- 1991 The writings of BrahmabandhabUpadhyay, Vol 1 Bangalore: United Theological College Toscano, Giuseppe, S.X.,

- 198O peretibetane di IppolitoDesideri, S.J. Roma: IstitutoItaliano per iImedioedextremooriente.

VANDE SACCIDANANDAM

("Canticle to the Trinity")

by

Brahmabandhab Upadhyay (1861-1907)

Refrain:

Vande saccidānandam–vande

Vande saccidānandam - vande

- . Bhōgilānchitayōgivānchitacharamapadam- vande, vande.

-

. Paramapurāanaparātparam

Pūrnamakhandaparāvaram

Trisangasudhamasangaudhamdurvēdam - vande -

. Pitrusavitruparamēshamajam

Bhavavrkshabījamabījam

Akhilakāranamikshanasrijanagōvindam -vande -

Anāhatasabdamanantam

Prasūtapurushasumahāntarm

Pitrusvarūpachinmayarūpasumukundam - vande -

Saccidōrmēlanasaranam

Shubashvasitānandaghanam

Pāvanajāvanavānivadana

Jīvanadam- vande

Refrain:

Worship to the saccidananda,

Worship to the saccidananda,

The Existent, the Knower, the Blissful

- The furthest goal, despised by the world, longed for by the holy ones

-

The Almighty, the ancient, the fullness, the undivided

Higher than the highest, the far and the near,

Related within, unrelated without,

The holy, the aware, whom intellect scarce can reach

-

The Father, inspirer, the unbegotten,

The seedless seed of the tree of being

From whose regard all this proceeds

The great Lord, the cause of all

The protector of the world -

The uncreated Son, the Word without end,

The great person, the image of the father

the essential wisdom, the savior

-

The blessed, the essential Felicity

Proceeding from the unity of being

And consciousness

The sanctifier, the swift, the revealer

Of the revealing Son,

The giver of life